The British Contagious Diseases Acts (1864, 1866, and 1869)

“It is men, only men, from the first to the last that we have to do with! To please a man I did wrong at first, then I was flung about from man to man. Men police lay hands on us. By men we are examined, handled, doctored.” – A prostitute’s account

The Contagious Disease Act, initially was passed in 1864 by the Parliament of the United Kingdom with the goal of preventing venereal diseases within the armed forces. This legislation essentially allowed for police officers to arrest women suspected of being prostitutes. Once arrested, the women were forced to endure medical checks for sexually transmitted infections. If they were in fact determined to be infected, they would be confined into a lock hospital until recovered—up to three months—or essentially served their sentence if they did commit any crime according to the existing laws.

The Contagious Diseases Act of 1864 was reformed the first time in 1866. The new Contagious Disease Act of 1866, worked to spread the jurisdiction of this legislation to more naval ports, districts, and army towns and even the civilian population—with a new goal to regulate prostitution in general. Furthermore, in the Act of 1866, period women found to be infected could be held in the lock hospital was extended to a whole year. It’s noteworthy to realize that within these acts to ostracize prostitutes, that no provision was made to prevent the clientele—military and other men from interacting with the sex workers.

Many advocates worked to get these acts repealed as they saw it as an injustice to the sex workers as well as a clear inequality between men women. One of the most notable figures in the fight against the Contagious Diseases Acts was Josephine Butler (1828-1906), who described such legislation as allowing for “medical rape”. The struggle was supported by the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts (LNA) that was established in 1869 by Elizabeth Wolstenholme (1833-1918) and Josephine Butler. The LNA did not only fight against the Contagious Diseases Acts; it was also involved in other important social and political issues.

On 1 January 1870 the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts published an article title “Women’s Protest” in the Daily News, which gave a detailed explanation of what exactly the LNA felt was unjust and unlawful about the Contagious Diseases Acts:

“2nd – because as far as women are concerned, they remove every guarantee of personal security which the law has established and held sacred, and put their reputation, their freedom, and their persons absolutely in the power of the police

4th – Because it is unjust to punish the sex who are the victims of a vice, and leave unpunished the sex who are the main cause, both of the vice and its dreaded consequences; and we consider that liability to arrest, forced medical treatment, and (where this is resisted) imprisonment with hard labour, to which these acts subject women, are the punishment of the most degrading kind.“

The article, signed by many well know women, summarized the critique of the LNA: the double standards of men, the fact that only woman (even though men were also responsible for the spread of venereal disease) were subjected to humiliating medical examinations, that if they were found to be infected they would be contained in lock hospitals for treatment, and that if women refused to comply with the police they could face imprisonment regardless of any possible financial, economic, social and emotional impact on the woman or her family. The LNA campaign finally brought the fall of the Contagious Diseases Acts. They found the unanimous support of a Royal Commission in 1871, and by years of lobbying convinced the British Parliament to suspend the Acts in 1883 and repeal them in 1886, thus ending legalized prostitution.

I think that the history of the Contagious Diseases Acts is important to remember in terms of today’s history in how laws and movements act to “end sex work”. I think often times, these ideas are detrimental to sex workers, and it’s not recognized that there is a receiving end within transactional sex. Much like the inequalities in 1864, in that men were not held accountable for their encounters with sex workers, when in fact they are considered to be “men of status”, men still aren’t held accountable for such actions. Instead, in 2018, we still continue to punish the sex worker with a criminal record a mile long for selling sex. I think this is rather in just, and furthermore, I don’t think we are ever going to successfully end prostitution, as it is the oldest profession, but we can make it safer for the women who are involved in transactional sex and I think that should be our focus- globally.

Alyssa Atwell, Quantitative Biology & Women and Gender Studies, Class of 2020

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “Contagious Diseases Acts.” Wikipedia, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contagious_Diseases_Acts (Accessed April 27, 2018).

- “The Contagious Diseases Act.” The Victorian Web. http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/contagious.html (Accessed April 27, 2018).

- “Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts,” Wikipedia, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ladies_National_Association_for_the_Repeal_of_the_Contagious_Diseases_Acts (Accessed April 27, 2018).

- Acton, William. Prostitution, Considered in Its Moral, Social and Sanitary Aspects in London and Other Large Cities and Garrison Towns. London: John Churchill & Sons, 1857.

- Vicinus, Martha. Suffer and Be Still: Women in the Victorian Age. Bloomington: Indiana Universitiy Press, 1994.

- Walkowitz, Judith. Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class, and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

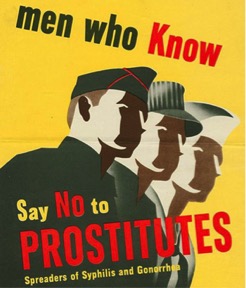

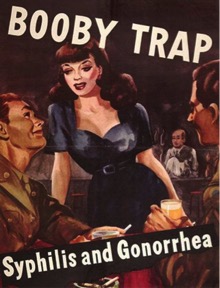

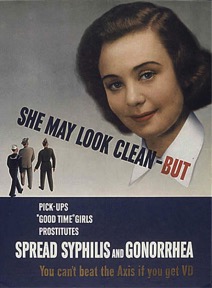

Images

that demonstrates the continuing stigma surrounding sex workers: “She may look clean but. . . “