National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) (1807-1928)

“Until we win! We demand the vote!” – NUWSS Slogan, 1913

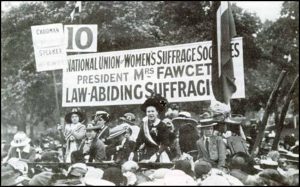

The British suffrage movement started already in the 1860s, much earlier than in most other European countries. Several local organizations became active ad demanded women’s equal right to vote, first on the local and then on the national level. But until 1897, when the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was founded by the merger of the National Central Society for Women’s Suffrage and the Central Committee, National Society for Women’s Suffrage, British women were not united in their struggle for the right to vote. The NUWSS became the leading moderate suffragist organization until 1919. Involving hundreds-thousands of women in the campaign to earn women the right to vote, the group was headed by Millicent Garret Fawcett, the president of the NUWSS.

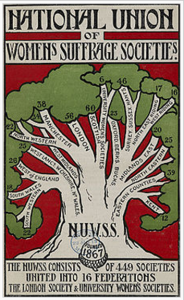

The NUWSS was primarily a middle- and upper-class women’s movement, but it did have some representation from working-class women. Women who had an interest in suffrage sent delegates to the NUWSS, and these representatives took the message of the benefits of the right to vote back to the women they represented. These women included textile workers, sweated laborers, and women who worked in mines. The NUWSS became the leading women’s suffrage organization in Britain and throughout Europe. By 1905, it had reached 305 constituent societies and by 1913 comprised over 500 branches united across 16 federations. By 1914, it had in excess of 500 branches throughout the country, with more than 100,000 members. The WSPU had only 2,000.

The NUWSS was considered a moderate suffragist organization. This meant they relied on non-violent and legal ways to get their message across and earn the right to vote for women. They sought to create change constitutionally. Other groups, such as the Suffragettes, who formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), which split in in 1903 from the NUWSS, were more militant and used more radical—and often illegal—forms of political activity and civil disobedience to reach their goal. The NUWSS held public meetings, organized petitions, wrote letters to politicians, published newspapers and distributed free literature. The main demand was for the vote on the same terms “as it is, or maybe” granted to men. It was thought that this proposal would be “more likely to find support than a broader measure that would put women into the electoral majority, and it might nevertheless play the part of the thin end of the wedge.” Its message was directed at the Liberal Party, who it was hoped would win the election s and introduce the right to vote for women.

The NUWSS leadership supportive Britain’s involvement in World War I. They believed, like NUWSS president Millicent Garret Fawcett, that being supportive of the British war efforts and providing all aid possible, would earn women respect from men and the state and thus help them gain the equal right to vote. The NWSU organized the war welfare for the families of soldiers and invalid veterans, the work of military nurses and the work of women in the war industries in the jobs men left behind to fight. Parallel to its war support, the NUWSS continued to campaign for the right to vote during the war and used its war work to their advantage by pointing out the contributions women had made in their campaigns.

After the end of World War I, members of the NUWSS and other women fighting for the right to vote didn’t get exactly what they wanted in terms of rights, in that, not all adult women were given the right to vote. A parliamentary committee decided in 1919 to abolish property qualifications for suffrage rights and gave all men over twenty-one and all women property owners (or wives of property owners) over 30 the right to vote. In the end, about six million women were enfranchised. However, the law excluded most women whose work as nurses or as industrial workers had been the most important during the war.

So, in 1919, the NUWSS renamed itself the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship and continued under the new leadership of Eleanor Rathbone the fight for equal suffrage. Later that year Rathbone persuaded the organization to accept a six-point reform program: (I) Equal pay for equal work, involving an open field for women in the industry and the professions. (II) An equal standard of sex morals as between men and women, involving a reform of the existing divorce law which condoned adultery by the husband, as well as reform of the laws dealing with solicitation and prostitution. (III) The introduction of legislation to provide pensions for civilian widows with dependent children. (IV) The equalization of the franchise and the return to Parliament of women candidates pledged to the equality program. (V) The legal recognition of mothers as equal guardians with fathers of their children. (VI) The opening of the legal profession and the magistracy to women. Ten years later, in 1928, the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship finally saw its hard work pay off in respect of the women’s suffrage, when women were given the same voting rights as men – allowing all women above the age of 21 to vote.

The NUWSS is still relevant today because it is where the women’s movement began. If it hadn’t been for the women in this organization, women today may not have the same voting rights or rights in general that they do today. This organization is not only an important part of European women’s history but is also important to women’s history in general. Groups like this is where the fight for women’s rights and feminism began. Without studying the history of feminism, we wouldn’t know how far we’ve come and why our situation is what it is today. Without studying groups like this, we might not have the groups we do today fighting for women’s rights. This group, and others like it, are early examples of how to organize around a cause and how to achieve political or social goals. These examples are important models for organizations today. The NUWSS is also important to study because it was a very influential organization in gaining women the right to vote and was the largest suffrage organization in Europe during this time. It had a huge influence on politics during this time and on history.

Bailey Alridge, Journalism and Political Science Major, Women’s and Gender Studies Minor, Class of 2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Allen, Taylor Ann. “Women and the First World War, 1914-1918.” Women in Twentieth-Century Europe, 6-20. New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2007.

- Fawcett, Millicent, “To the Members of the National Union,” The Common Cause, 7, August, 1914, in Women, The Family, and Freedom: The Debate in Documents, ed. Susan Groag Bell and Karen M. Offen, 260-261. Stanford: Stanford University Press: 1983.

- Fuchs, Rachel G. and Thompson, Victoria E. Women in Nineteenth Century Europe, 137-154 and 162-176. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005

- “National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Union_of_Women%27s_Suffrage_Societies (Accessed 9 April, 2018)

Images