The British Voluntary Aid Detachment (V.A.D.) (1909-1918)

“The attack has begun. ‘At 3.15 this morning… on a front of two miles…’ So that is why the ward is so empty and the ambulances have been hurrying out of the yard all day. We shall get that convoy for which I longed. When the ward is empty and there is, as now, so little work to do, how we, the women, watch each other over the heads of the men! And because we do not care to watch, nor are much satisfied with what we see, we want more work. At what a price we shall get it…” – Enid Bagnold

The First World War killed an estimated 37 million people. During this first industrialized “total war,” which blurred the boarders between the home front and the battle front, women became active supporters of the war and witnessed the horrors of war. But in this time of great peril for all involved belligerents, also new opportunities emerged for women, because they were needed more than ever before in all war efforts at the home front and the front to replace the men mobilized for the military.

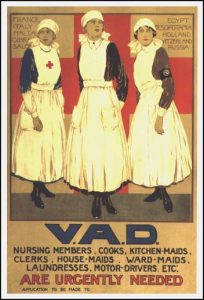

One specific example was the Voluntary Aid Detachment (V.A.D.), through which British women volunteered to serve the wounded and sick soldiers under the Red Cross and Order of St. John in both field hospitals and other medical facilities within Britain and behind the frontlines in Europe. The V.A.D. was formed in August 1909 with the War Office issuing the Scheme for the Organization of Voluntary Aid for England and Wales in an effort to prevent the shortage of nurses during times of war. As volunteers, these V.A.D. women worked without pay, meaning their backgrounds primarily consisted of middle class or upper class patriotic British women.

Initially trained in providing meals and nursing the wounded, the number of V.A.D. workers swelled with the start of World War I to 40,000 members across 1,800 detachments. They provided a variety of crucial wartime services including nursing assistants, ambulance drivers, chefs and administration roles. Though membership was not limited to women, the vast majority of volunteers were women. By the end of the war in 1918, these women proved themselves invaluable to the war effort. Of the 126,000 that had served 243 were killed, 364 decorated and 1,005 mentioned in letters of dispatches, paving a way for a greater inclusion of women in both military and medical professions for generations to come.

Trained professional military nurses did not always view these volunteers in a positive light as the idea of losing their profession to these new women after the war left visible tension. For example, Vera Brittain who worked as V.A.D. nurse wrote in her 1933 memoir Testament of Youth, observed:

“I read in the official Report by the Joint War Committee of the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. Johnthe following words – a little pompous, perhaps, like the report itself, but doubtless written with the laudable intention of reassuring the anxious nursing profession: ‘The V.A.D. members were not… trained nurses; nor were they entrusted with trained nurses’ work except on occasions when the emergency was so great that no other course was open.’”

Despite claims that these V.A.D. nurses only performed the duties of trained nurses when needed, the reality of the war was that their services were desperately needed both at home and abroad. More often than not, this put the women mere miles away from the front lines to deal with the most gruesome of injuries inflicted in war by new technologies such as explosive artillery, mechanized weapons of war, machine guns and chemical warfare. Once the war ended in 1918, many members of the V.A.D. entered a variety of professions that included writers, poets, actresses, and other jobs that were not directly medical in nature.

The women themselves had to undergo strict rules and regulations which were subject to change as the influx of new volunteers during the war transformed the dynamic of everyday life regarding military care. While some considerations were practical, others were an attempt to control behavior of these women coming from a variety of ages and experiences. Being a V.A.D. volunteer would be first job for some of these middle and upper-class women. Instructions sent out in July 1915 for all new hospital V.A.D.s included:

“1. …If the skin is broken, however slightly, it should be covered with gauze and collodion before assisting at an operation or doing a dressing… 3. All powder, paint, scent, earrings, or other jewelry, etc., should be avoided, as the using of such things invites criticism, and may bring discredit to the Organisation.”

Other conditions included keeping their white uniforms clean and tidy, which would have been nearly impossible in situations of taking care of dire injuries. Even though these women were performing medical assistance when needed, they were held to a standard that placed them as being the face of the volunteer organization.

As the war-ravaged Europe, British military leaders called for reform to make it easier to volunteer as seen in the 1916 statement, “A simple way out of the difficulty is a course of ten lectures and ten instructions in first-aid and nursing.” (Davidson, 98) Rather than train for a few months before deployment, these lessons could be completed in a fraction of the time, though no amount of training would fully prepare them for the horrors of war. A commonality of them found across personal accounts of V.A.D. nurses was that the experiences would last with them for a lifetime.

This often overlooked subject continues to fade from popular memory as each generation is further removed from the experiences of mass warfare. These women carried themselves with dignity and professionalism as they witnessed some of the worst injuries in modern history. Furthermore, the compulsion of these British women to act demonstrated the agency of women at the time of World War I as active participants. Undoubtedly, these women saved a great number of lives and their contributions to humanity should be acknowledged in face of the atrocities of war. While we as a society can hope to avoid such conflicts in the future, the efforts of these women teach the value of selflessness and the true meaning of loss through war as detailed by their memoirs.

Eric Schmidt, History with a concentration in Modern European studies, Class of 2018

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “Voluntary Aid Detachment.” QARANC, at: http://www.qaranc.co.uk/voluntary-aid-detachment.php (Accessed April 14, 2018).

- “Women’s Roles on the Front Line.” BBC News. March 06, 2014. Accessed April 14, 2018. http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/0/ww1/26374718 (Accessed April 14, 2018)

- Bagnold, Enid. A Diary Without Dates, 1-146. London: W. Morrow & Company, 1918.

- Brittain, Vera. Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Story of the Years 1900-1925. London: Gollanz, 1933.

- Davson, Win. “Voluntary aid detachments.” Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland15, no. 2 (1993): 98-100.

- Light, Sue. VAD Life, at: http://www.scarletfinders.co.uk/183.html (Accessed April 14, 2018).