Jane Austen (1775-1817)

“It isn’t what we say or think that defines us, but what we do.” —Sense and Sensibility

Jane Austen’s life is a testimony of both the obstacles faced by female writers of the eighteenth century and the societal pressure for marriage during the time. Born on December 16, 1775 in Steventon, England, Austen showed promise of becoming a writer at a young age for as a child, she wrote short stories and plays for her family. In her twenties and thirties, she began writing novels, such as Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Pride and Prejudice (1813). While Austen struggled to get her works published as a female writer, she demonstrated persistence by continuing to write and pursue publication. More significantly, Austen defied eighteenth and early nineteenth century societal expectations for women through her career as a writer and life as a single woman.

Jane Austen was born in Steventon, Hampshire, on 16 December 1775. For much of Jane’s life, her father, George Austen (1731–1805) served as the rector of the Anglican parishes at Steventon, and a nearby Deane. He came from an old, respected, and wealthy family of wool merchants, but he and his two sisters were orphaned as children and had to be taken in by relatives. George Austen entered St John’s College at Oxford University on a fellowship, where he most likely met his later wife Cassandra Leigh (1739–1827). She came from the prominent Leigh family; her father was rector at All Souls College at Oxford University, where she grew up among the gentry. In 1768 Jane Austen’s parents took up residence in Steventon. Henry was the first child to be born there, in 1771. In 1773, Cassandra was born, followed by Francis in 1774, and Jane in 1775. In 1783, Austen and her sister Cassandra were sent to Oxford to be educated by Mrs Ann Cawley who took them with her to Southampton when she moved there later in the year. In the autumn both girls were sent home when they caught typhus and Austen nearly died. Austen was from then home educated, until she attended boarding school in Reading with her sister from early in 1785 at the Reading Abbey Girls’ School, ruled by Mrs La Tournelle.

Although Jane Austen’s novels have become famous literary works, she faced rejection throughout her life. Her endeavors began in 1797 after she completed her novel First Impressions, which was later renamed Pride and Prejudice. When Austen’s father tried to get her novel published, the publisher Tom Cadell rejected the request. In 1803, she gave her brother Henry permission to submit her novel Susan to another publisher. Henry sold the copyright for 10 pounds, but the publisher Benjamin Crosby never fulfilled his promise. The opposition she experienced and the need men’s in getting her works published demonstrate the prejudice against female writers during the eighteenth century.

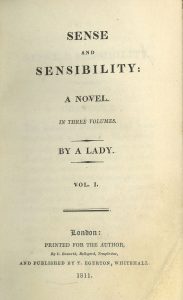

Despite the rejection that she received from some publishers, Austen continued to work towards the goal of publication and never abandoned her writing. Like other female writers of the time, she had to be incredibly persistent and resorted to writing under pseudonyms. For example, in 1809, she wrote to Benjamin Crosby under the name Mrs. Ashley Denni, a witty pseudonym with the acronym “M.A.D.,” to pressure him to publish her book. Since Crosby owned the copyright to her work and she could not afford to purchase it back, Austen needed to pressure him to set a date to publish her work. No doubt that this predicament would cause her anger and frustration, hence the pseudonym “M.A.D.” It was not until 1816 that her brother Henry purchased back the copyright to Susan. Finally, between the years of 1811 and 1816, she anonymously published Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814), and Emma (1815). Austen signed her novels as being “by a lady,” making her gender but not her name known to the public. The significance of her work being anonymous was that she showed to the male audience that woman could write well while adding a sense of mystery. Austen’s identity was not revealed until after death by her brother. When her authorship became public, her works received high praise by the theologian Richard Whately, who declared, “we suspect one of Miss [Austen’s] great merits in our eyes to be, the insight she gives us into the peculiarities of female characters.” Whately’s remark acknowledged how Austen’s gender contributed to her writing and gave her work insight that could male writers could not accomplish. In this way, her gender can be seen as both a strength and an obstacle in her path to success as a writer.

Another important aspect of Jane Austen’s life that defied eighteenth century gender roles and expectations for women is that she never married. At first, it may seem paradoxical that a woman who never married wrote novels about romance and marriage. However, she acted upon her belief that women should not marry if they felt no love towards their husbands. In a letter to her niece Fanny Knight on November 18, 1814, Austen expressed her opinions on love:

There are such beings in the world, perhaps one in a thousand, as the creature you and I should think perfection; where grace and spirit are united to worth, where the manners are equal to the heart and understanding; but such a person may not come in your way, or, if he does, he may not be the eldest son of a man of fortune, the near relation of your particular friend, and belonging to your own county.

Austen’s letter revealed several insights, including her belief that a woman can fall in love with a man not for his wealth. The letter also suggested that marriage should be about love rather than financial security or convenience. In Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility, Austen portrays the pressure that women faced to marry and how this pressure led women to enter marriages for social mobility, financial security, or societal and family pressure.

During two instances in Austen’s life, she had to make decisions regarding the prospect of marriage. There is speculation that Jane Austen fell in love with a man named Tom Lefroy in 1795 when she was 20 years old. Both Austen and Lefroy’s families viewed the relationship as impractical since neither of them were wealthy. Perhaps the memory of Lefroy had inspired her letter to Fanny because she was not able to marry the man that she loved. Later in, 1802 a man named Harris Bigg-Wither proposed to Austen. Although she initially accepted his proposal, she called off the engagement the following day. Austen’s withdrawal from the engagement proves her strong and independent character. If she had married Harris Bigg-Wither, she would have had financial security since he was an heir to a large estate. However, what Austen gained from being single was the freedom to write her novels.

Jane Austen remains a legacy today because of her literary contributions as well as rebellion of eighteenth century societal expectations. Her realist novels provide insight into the lives and relationships of women in the English upper and middle class of her time. Ultimately, Jane Austen’s own life is an admirable story of struggle, defiance, and success.

Kate Nicholson, Biology and History, Class of 2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “Jane Austen Biography.” The Biography.com website, at: https://www.biography.com/people/jane-austen-9192819. (Accessed April 12, 2018).

- “Letters of Jane Austen.” The Republic of Pemberly, at: http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/brablt15.html. (Accessed April 13, 2018).

- Looser, Devoney. The Making of Jane Austen. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

- Southam, B. C., ed. Jane Austen: The Critical Heritage, 1812–1870. Vol. 1. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1968.

- Warren, Renee. “Jane Austen Life Timeline.” Jane Austen, at: https://www.janeausten.org/jane-austen-timeline.asp. (Accessed April, 13, 2018).

Images