Catherine Macaulay (1731-1791) and the English “Bluestocking Circle”

“Of all the various models of republics, which have been exhibited for the instruction of mankind, it is only the democratical system, rightly balanced, which can secure the virtue, liberty, and happiness of society”

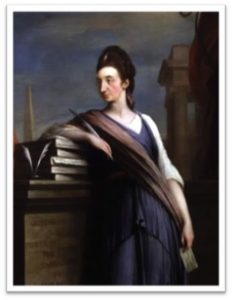

Catherine Macaulay (1731-1791) was an English historian and radical political writer most famously known for her substantial eight-volume work A History of England from the Accession of James I. to that of the Brunswick Line, published between 1763 and 1783. In it Macaulay argued that the history of the English Civil War was a result of the struggle of the common people to retain their liberties against the monarchy. Macaulay belonged to a small group of educated upper class women called the “Bluestocking Circle” that emerged in England around 1750. These women asserted their intellectual abilities and right to educational access at a time when few women could do so.

Catherine Macaulay was born in Kent, England on March 23 as the daughter of John Sawbridge and his wife Elizabeth Wanley of Olantigh. Her father was a landed proprietor from Wye, Kent, whose ancestors were Warwickshire yeomanry. Raised in an upper-class family, she was educated privately at home by a governess and a Greek scholar, Elizabeth Carter, who met Catherine at a function in Canterbury. Little is known about Macaulay’s early life, though she was described in an acquaintance’s letter as a “very sensible and aggregable woman.” In 1760 Macaulay married a Scottish physician, Dr. George Macaulay (1716–1766), and they moved to London and remained married for six years until his death in 1766. They had one child together, Catharine Sophia.

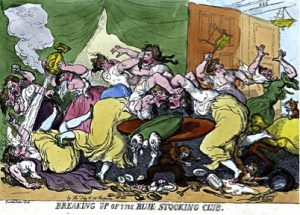

During the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, understood as an intellectual, social, and cultural movement, reasoning was seen as the primary source and legitimacy for authority. Enlightenment thinkers discussed new and at that time radical political and philosophical ideas that emphasized freedom, democracy, and reason as primary values of society. The enlightenment was mainly a movement of educated upper and middle-class men. Women were rarely involved in their debates. The Bluestocking Circle was one exception. These educated and privileged women refused to accept the exclusion of their sex from the life of the mind, “the republic if letters,” advocating their right to be writers, artists, historians, and thinkers. They also criticized main aspects of women’s lives, especially the degrading education of women during the 18th century and the increasing restriction of female job opportunities.

The women in the Bluestocking Circle included Anna Letitia Barbauld (1743–1825), poet and writer; Elizabeth Carter (1717–1806), scholar and writer; Elizabeth Griffith (1727–1793), playwright and novelist; Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807), painter; Charlotte Lennox (1720–1804), writer; Catharine Macaulay (1731–1791), historian and political polemicist; Elizabeth Montagu; Hannah More (1745–1833), religious writer; and Elizabeth Ann Sheridan (née Linley) (see image 2). They published advice books, novels, and edited women’s journals. These texts were read and discussed by other educated women in private reading circles and associations or their salons at home, open to likeminded friends.

Although Catherine Macaulay, who died in Binfield in 17911, and the Bluestocking Circle were privileged, elite women who were fortunate to have access to education, they made their voice heard during a time in which women were viewed as subordinate. These women supported one another, engaged in intellectual conversations, and demanded better education and job opportunities for women. The actions of Catherine Macaulay and the Bluestocking Circle led society to question gender conventions and relations during the eighteenth century, which would ultimately lead to the resurgence of a powerful women’s suffrage movement.

Leeza Mason, Biology Major, Chemistry and History Minors, Class of 2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “Online Library of Liberty.” Catharine Macaulay – Online Library of Liberty, at: http://oll.libertyfund.org/people/catharine-macaulay. (Accessed April 22, 2018).

- Bell, Susan G. and Karen M. Offen, eds. Women, the Family, and Freedom: The Debate in Documents. vol. 1: 1750-1880, 31-49. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1983.

- Goodman, Dena, “Women and the Enlightenment.” In Becoming Visible: Women in European History, ed. Renate Bridenthal, Susan Mosher Stuard and Merry E. Wiesner, 233-262. Third edn. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

- Green, Karen. “Catharine Macaulay.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/catharine-macaulay/ (Accessed April 22, 2018).

- Macaulay, Catherine. The History of England from the Accession of James I. to that of the Brunswick Line, 8 volumes. London: J. Nourse. 1763-1783.

- Myers, Sylvia Harcstark. The Bluestocking Circle: Women, Friendship, and the Life of the Mind in Eighteenth-century England. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Images