Déclaration des Droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne (Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen) (1791) by Olympe de Gouges

“Man, are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex?” – Déclaration

The French Revolution (1789-1798) was a period not only of great conflict, upheaval and war, but also of great ideas. I believe that these ideas were as revolutionary, if not more revolutionary, than any battles or wars fought during the same time period. Most thinkers, philosophers, and writers of the time proposed new ideas on human nature and the rights and laws of citizens. However, these debates and ideas were mostly genderless, and most ideas of the time demanded for the rights of man but asked very little for the change of social standing of women in society. The rights for women therefore were largely overlooked, however there remained a strong number of individuals who wrote for and advocated for the rights of women. One of these individuals went by the name of Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793), and in one of her most famous works, the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen (Déclaration des Droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne), 1791 she attacks the ideas of the existing male dominated social structure and mandates a set of demands that provide more rights for woman.

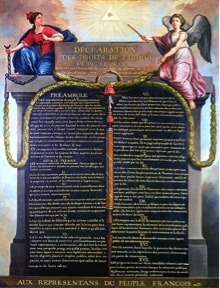

Her Declaration was a direct response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 (Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen) from August 1789 by the France’s National Constituent Assembly. The Declaration was Influenced by the enlightened idea of universal “natural right. It outlines a series of human rights that were deemed to be universal for all, but in fact only included men. De Gouges responded with her 1791 Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, which is dedicated to Queen Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) and starts with a letter to queen in form of a petition on behalf of the French women. The letter presents a list of grievances and requests for specific and detailed change and emphasizes that “This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society”.

The text of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen itself that follows the letter is structured parallel to the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Some articles are kept almost identical to the original, but De Gouge’s declaration adds upon the original by modifying and updating each article in a way that includes women.

De Gouges opens her Declaration with the famous quote, “Man, are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex?” She demands that her reader observe nature and the rules of the animals surrounding them—in every other species, sexes coexist and intermingle peacefully and fairly. She asks why humans cannot act likewise and demands (in the preamble) that the National Assembly decree the Declaration a part of French law. In the preamble to her Declaration, de Gouges mirrors the language of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and explains that women, just as men, are guaranteed natural, inalienable, sacred rights—and that political institutions are set-up with the purpose of protecting these natural rights. She closes the preamble by declaring that “the sex that is superior in beauty as it is in courage during the pains of childbirth recognizes and declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen.”

The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.” The first article of Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen responds: “Woman are born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility.” Articles II and III extend the articles in the Declaration of Independence to include both women and men in their statements. Article IV declares that “the only limit to the exercise of the natural rights of woman is the perpetual tyranny that man opposes to it” and that “these limits must be reformed by the laws of nature and reason”. In this statement, de Gouges is specifically stating that men have tyrannically opposed the natural rights of women, and that these limits must be reformed by the laws of a political organization in order to create a society that is just and protects the Natural Rights of all. Also the following articles are each powerful and each could warrant a complete discussion on itself.

De Gouges opens her postscript to the Declaration with the statement: “Woman, wake up; the tocsin of reason is resounding throughout the universe: acknowledge your rights. In the first paragraph of this postscript, she implores women to consider what they have gained from the Revolution – “a greater scorn, a greater disdain.” She maintains that men and women have everything in common, and that women must “unite under the banner of philosophy.” She declares that whatever barriers women come up against, it is in their power to overcome those barriers and progress in society. She goes on to describe that “marriage is the tomb of trust and love” but fails to write laws that apply to unmarried women—she leaves this to men, but implores men to consider the morally correct thing to do when creating the framework for the education of women.

The Declaration interestingly ends with a social contract between man and women in marriage. At first glance, the inclusion of this part seems strange. However, when viewing the broader reach of de Gouges Declaration, one realizes that the true importance of this part is its relevance for all those women across France who read this and hope for a change of their legal status in marriage. It was intended to serve as a model for a private contract of married couples.

De Gouges letter is powerful document of the debate about the “women’s question” during the French Revolution. It serves as an important historical testament to the lasting effects on women’s movements around the world and much after her time. Her understanding of women’s rights and her writing has influenced the struggle for women’s rights long-lastingly.

Nikhil Komirisetti, Computer Science Major, Statistics and Neuroscience Minor, Class of 2020

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “Declaration of the Right of Man and the Citizen, 26 August 1789,” at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b52410.html (Accessed: 23 April 2018)

- “Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1789,” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_of_the_Rights_of_the_Man_and_of_the_Citizen_of_1789 (Accessed: 23 April 2018)

- “Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen,” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_of_the_Rights_of_Woman_and_of_the_Female_Citizen (Accessed: 23 April 2018)

- “Olympe de Gouges, The Declaration of the Rights of Woman, 1792,” in Women in Revolutionary Paris, 1789-1798, ed. Darline Gay Leyy, Harriet Branson Applewhite and Mary Duham Johnson, 87-96. Urbana Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1980.

- Fuchs, Rachel and Victoria Thompson. Women in Nineteenth-Century Europe, 5-23. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Levy, Darline Gay and Harriet B. Applewhite. “A Political Revolution for Women? The Case of Paris,” in Becoming Visible: Women in European History, ed. Renate Bridenthal, Susan Mosher Stuard, Merry E. Wiesner, 265-292. Third edn. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

- Offen, Karen. European Feminisms 1700-1950: A Political History, 50-76. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Scott, Joan Wallach. “French Feminists and the Rights of ‘Man’: Olympe de Gouges’s Declarations.” History Workshop, no. 28 (1989): 1-21.

Images