Eleanor Rathbone (1872-1946)

“We can demand what we want for women, not because it is what men have got, but because it is what women need to fulfill the potentialities of their own natures”

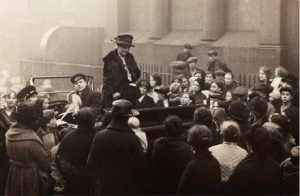

Few women, if any, hold political positions without being judged due to their gender. There was a time, though, when women were not even present in the political sphere. Pioneering moderate feminist Eleanor Rathbone (1872-1946) became one of the first female members of the British Parliament in 1929. She was a long-term campaigner for social justice, family allowance and for women’s rights, a leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), and since 1919, when Millicent Fawcett (1847-1929), its long-term leader retired, became the presidency of the NUWSS, renames to National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship.

One of the youngest of her siblings, Rathbone was born in Princes Gardens, London to Emily Lyle and William Rathbone in May 1872. Her father was a Liberal member of the British Parliament from 1868 to 1895. Because of her father’s political involvement, she met at an early age various intellectuals and politicians who visited him and listened to their discussions. Rathbone’s education was conducted in her home until she was finally able to persuade her family to allow her to study in Somerville College, Oxford in 1893, where she became known as “the philosopher.” After graduation, Rathbone worked alongside her father to investigate social and industrial conditions in the industrial North-English city Liverpool, until he died in 1902. She became a volunteer for the Liverpool Central Relief Society. There, she saw impoverished families and helped them plan ways to overcome their poverty.

Since the 1890s she Increasingly had become active for social reform and women’s rights. She believed that there needed to be not only legal equality, but also an economic change to women’s status in society. Already in 1895, she became the secretary of the Liverpool Women’s Suffrage Society, she co-founded with Nessie Stewart-Brown 1864-1958), and of the Women’s Industrial Council. In Liverpool. In 1903, she began working with the Victoria Women’s Settlement where she met Elizabeth Macadam (1871-1948), the appointed warden of the settlement. Macadam was a leading figure within the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), founded in 1897. Macadam played also an important role in the development of professional social work of middle and upper-class women. Together, these two women, who became close friends, would become very active in the local women’s movement of Liverpool. In 1906, women finally were allowed to campaign for positions in the Liverpool City Council, which Rathbone did in 1909 as an Independent candidate. With the aid of the Victoria Women’s Settlement she won the election and held the position until 1935.

Rathbone supported the suffrage movement, but not the militant tactics that the suffragists of the Women’s Social and Political Union, founded in 1904, used. She believed in the moderate strategy of the suffragists, supported the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and wrote a series of articles for NUWSS magazine The Common Cause. In 1913 she co-founded the Liverpool Women Citizen’s Association to promote women’s involvement in political affairs together with Nessie Stewart-Brown (1864-1958).

After Britain had declared war against Imperial Germany, Rathbone organized the Town Hall Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association (today known as SSAFA, the Armed Forces charity) to support wives and other dependents of the volunteering soldiers. When World War I ended and Rathbone saw soldier’s wives and widows struggle as a result of lack of funds and provisions provided to them, she started speak out against the family wage system, instead advocating for a family allowance system. Rathbone suggested that a family allowance should be paid to women as mothers, which would provide for each child in the family. Eventually her family endowment plan was incorporated into the Family Endowment Act in 1945 by a Labor government, despite its challenge of the dominating ideal of the patriarchal male breadwinner family. With this suggestion she also hoped to fight the argument that men needed higher wages as breadwinners of the family.

At the end of World War I, when British women over 30 finally got the right to vote in 1918 (British women under 30 had to wait until 1928), Rathbone formed the “1918 Club” in Liverpool, reputedly the oldest women’s forum still meeting, to support an active role of women in politics. In 1919, when Millicent Fawcett (1847-1929), the long-term leader of the NUWSS retired, Rathbone took over the presidency of the NUWSS, renamed to National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship.

She contested in the 1922 general election for the British Parliament as an Independent candidate at Liverpool East Toxteth against the sitting Unionist MP and was defeated. Finally, in 1929Elenore Rathbone entered British Parliament as an independent MP for the Combined English Universities. In one of her first speeches in the she parliament she criticized the British colonialism and its policy towards women. During the Great Depression, she campaigned for cheap milk and better benefits for the children of the unemployed. Rathbone also realized the danger of Nazi Germany early on. In the 1930s joined the British Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi Council to support human rights. In 1936 she began to warn about a Nazi threat to Czechoslovakia. She became an outspoken critic of appeasement in the British Parliament. She denounced British complacency in Hitler’s remilitarization of the Rhineland, the Italian conquest of Abyssinia and the British “neutrality” in the Spanish Civil War, which refused support a democratic elected government attacked by facists.

Eleanor Rathbone became one of the first female parliamentary politicians in interwar Britain. She dedicated her work to social reform and helped push women’s issues to the forefront while she was in office. She was the only woman in parliament for a while, but she held her position and did not allow the conservative members to push her out. Her biggest contribution was her work for a family endowment that supported the wives. Instead of benefiting the husbands, the women got the support of the Family Endowment Act of 1945.

Carina Ochoa, Chemistry and Women’s and Gender Studies, Class of 2018

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “Eleanor Rathbone.” Wikipedia, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleanor_Rathbone (Accessed 22 April 2018).

- “Family Endowment and the ‘New Feminism’” in Women, the Family, and Freedom, ed. Susan Groag Bell and Karen M. Offen, 318-327. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983.

- Fuchs, Rachel and Victoria Thompson. Women in Nineteenth-Century Europe, 15-37. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Pedersen, Susan. “Rathbone, Eleanor Florence (1872–1946), Social Reformer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, at http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-35678. (Accessed 22 April 2018).

Images