Gertrud Scholtz-Klink (1902-1999)

“Only she can be strong who knows sorrow and deprivation”

Gertrud Scholtz-Klink (1902-1999) was the Reichsfrauenführen (female leader) of the National Socialist Women’s League (Nationalsozialstische Frauenschaft, NSF) and the umbrella organization of the German Women’s Enterprise (Deutsches Frauenwerk, DFW) during the Third Reich (1933-1945). She was with these functions the most influential women in Nazi Germany.

Scholtz-Klink was born in February 1902 in Baden, a region in southern Germany, as the daughter of a surveyor, but her father died already in 1910. After finishing secondary school she completed an apprenticeship and worked as a journalist. She married in 1920 Eugen Klink, the district leader of the National Socialist Workers Party (NSDAP) in Offenburg, who died in 1930 during an election event at a heart attack. This marriage had four children. Already in 1929 Scholtz-Klink had officially joined the Nazi Party at the age of twenty-seven, the Nazi Party appointed her as the Party women’s leader in Baden. Two years later she married the doctor Günther Scholtz. This marriage lasted until 1937. After the divorce of Günther Scholtz, she married in December 1940, the SS Obergruppenführer August Heißmeyer (1897-1979), whom she had met professionally. Her third husband brought six children into the marriage. Her last child, by August Heißmeyer, was born in 1944.

After the Nazi Party seized power in 1933, according to historians Eleanor S. Riemer and John C. Fout, one of the first priorities was to organize women by declaring that, “All women’s organizations were ordered to accept Nazi leadership or disband.” Most secular women’s organizations had dissolved themselves or were abolished in 1933 and integrated under the German Women’s Enterprise, which consisted of a female membership of 2.3 million. Scholtz-Klink’s ideal Aryan image and her role as a mother to eleven children helped her and the Nazi Regime to emphasize that the primary role of German women was motherhood.

The Nazi women’s organizations created programs to educate young women and girls on household management, maternal health, child-care, sanitation, cooking, home economics, etc. The establishment of these programs, according to historian Ann T. Allen, reiterated that the “prime duty of the female citizen was to bear healthy children who would ensure the future of their nation.” Scholtz-Klink emphasized this separate sphere of men and women while addressing German women in her “Deutsch sein—heißt stark sein” (To Be German Is to Be Strong) speech from 1935, published in 1936 in the Frauen-Warte, the magazine of the NSF.

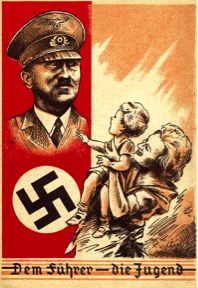

In this speech, Scholtz-Klink called on German women to become “mothers of the nation,” not just to their own children, but also to all those who need help. Becoming “mothers of the nation” would unite Aryan German women and grow a stronger nation through women’s service as mothers. Scholtz-Klink states that though “the deepest calling we women have is: motherhood,” between the years of 1918 to 1933, motherhood was seen as a burden and sacrifice. During those years, mothers did not subordinate themselves to the ideal that motherhood was her “contribution to the right of her people to survive.” The Nazi regime focused heavily on encouraging marriage and childbirth due to fears of falling birth rates that threatened military readiness. Throughout her speech, Scholtz-Klink supports Nazi ideologies regarding women’s roles in the survival of the nation. Her complete alignment with Hitler’s ideologies of separate spheres earned her the title in Britain of “the Perfect Nazi Woman.”

Although considered the top female leader in the Third Reich as Reichsfrauenführen, Scholtz-Klink had little influence in the traditional, male-dominated political sphere. However, she did have a huge influence over half of the German population: the women. The NSF and DFW infiltrated the everyday lives of German women with Nazi ideologies using propaganda, newspapers, speeches, and a separate women’s magazines like the NS Frauenwarte and Mutter and Kind (Mother and Child). Scholtz-Klink summarized the aim of Nazi policy towards women as follows: “Our job (and we did it well) was to infuse the daily life of all German women—even in the tiniest villages—with Nazi ideals.”

The contradictions embedded within Gertrud Scholtz-Klink powerful role as Reichsfrauenführerin during a totalitarian regime that viewed women as separate and inferior is often overlooked when studying this period. As the top female leader of the Third Reich, Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was fully involved in and thus responsible for the murderous policy of the Nazi regime. In order to understand Hitler and Nazi Germany’s reign over Europe, we must discuss also women’s involvement.

Kayla Travis, Exercise and Sport Science major and History minor, Class of 2018

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Allen, Ann T. Women in Twentieth-Century Europe, 42-59. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- Diehl, Guida. “A New Type of Woman.” In European Women: A Documentary History 1789-1945, ed. Eleanor S. Riemer and John C. Fout, 106-111. London: Schocken, 1980.

- Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, “Deutsch sein — heißt stark sein“ (To Be German Is to Be Strong). Rede der Reichsfrauenführerin Gertrud Scholtz-Klink zum Jahresbeginn,” N.S. Frauen-Warte 4 (1936), 501-502.

- Teichmann, Jennifer S. “A Triumvirate of Women in the Third Reich: Leni Riefenstahl, Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, and Winifred Wagner.” PhD diss., Central Missouri State University, 1999.

Images