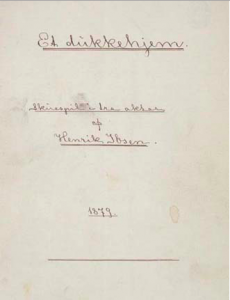

Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) and his play A Doll’s House (1879)

“Our home has been nothing but a playroom. I have been your doll-wife, just as at home I was papa’s doll-child; and here the children have been my dolls” – A Doll’s House

Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) made a true name for himself in the mid-nineteenth century when he tackled the traditional marriage model and the role of the woman in the home with the play A Doll’s House, first performed in Copenhagen, Denmark in December 1879. Ibsen’s character Nora shocked contemporary audiences by leaving her husband and children in an effort to find herself—an endeavor largely unheard of for the time period. Nineteenth century women were supposed to stay home and contentedly care for their husbands and children. Ibsen’s direct critique of this social norm put him at the center of controversy on gender and the role of women during a time when many feminist women’s organizations were being created in Northern and Western Europe.

Henrik Ibsen was born into a well-off merchant family in Skien, Norway in 1828. Following his marriage to Suzannah Thoresen, he moved his family to Italy in 1858 after struggling to find financial success. Over the following 27 years, Ibsen lived in a sort of self-imposed exile in Italy and Germany before returning to his native Norway prior to his death in 1906. Though Ibsen wrote the majority of his work while living in Italy or Germany, he often used Norway as his setting. His plays were controversial both in content and dramatic style. Nineteenth century theater was expected to reflect a model of a world with strict morals that conformed to society’s ideas of family life and propriety. However, Ibsen rarely conformed to this expectation and used his plays as a vehicle for social critique. Though he never directly called himself a feminist, many of Ibsen’s writings, including his most prolific, A Doll’s House, revealed that he had put much thought into gender relations and norms. His ideas reflected the growing formation of women’s organizations dedicated to suffrage and equal political and social rights at the end of the century.

Ibsen’s A Doll’s House is perhaps his biggest statement regarding women and gender relations. The play centers on the Helmer family: Nora, Torvald, and their children. Ibsen demonstrates the inequality in the power dynamic between Nora and Torvald in the beginning of the play. Torvald would be affectionate to Nora, but by referring to her his little “lark” and “squirrel” while simultaneously chastising her for spending too much on Christmas gifts or eating macaroons. To Torvald, Nora was always his “little” something, seemingly symbolizing both his possession of her and his view of her as less than a full human being. Through the resurfacing of her old friend Mrs. Linde and the uncovering of her long term lie to Torvald about a loan she took out to help them financially, Nora comes to the realization that she has been a bystander in her own marriage and family. After realizing that she had merely been an accessory to Torvald and prior to her marriage to her father, Nora decides to leave her family and set out on her own.

The play challenged core societal ideas about the family and roles of women and men in relationships. Nineteenth century norms still confined women to the domestic sphere and generally viewed women as frivolous and incapable of making difficult or complicated decisions. Nora’s character directly challenges this notion in that she has made what might have been considered an entirely masculine decision in taking out a secret loan behind her husband’s back. Nora’s sudden realization that she was not actually happy with her life and was simply playing a role was threatening to many contemporary conservative men. She represented women abandoning their husbands and children and signified the breakdown of the family.

In the end, Nora leaving her children was perhaps most difficult for contemporary viewers to grasp, as women were meant to be primary caregivers for children out of their natural instincts. Ibsen critiques the nineteenth century ideal of marriage with this play and demonstrates—through Nora—how a life without any individuality or choice is unfulfilling and even empty. This bold critique certainly earned Ibsen a reputation for being controversial, but as society progressed the play and Ibsen’s other works became more and more popular. By the twentieth century, A Doll’s House was the world’s most performed play.

Ibsen and A Doll’s House remain very much relevant today for the message it sends about social responsibility and recognizing our own societal positions. Ibsen could have easily written plays that followed the very rigid nineteenth century theatrical “rules,” but instead he chose to use his writing talent to call attention to issues within society no matter the discomfort associated with them. Though some women’s organizations were becoming more and more prevalent at the time of Ibsen’s publishing, most suffrage and equal rights groups weren’t in full swing until the 1880s and 1890s. Ibsen must have been aware of and probably welcomed the controversy that would surround this play. Ibsen demonstrates that, even if we aren’t part of a particular group or demographic, it is still important to evaluate their place within our society and see where we may improve. Likewise, Nora’s realization of her station in life as an accessory to her husband remains very relevant in modern society. I believe that without coming to terms with our own political, social, or economic realities, we remain powerless in changing them.

For anyone interested in a more easily accessible version of the play, I recommend the 1973 film adaptation of A Doll’s House, which can be found on YouTube.

Jessica Thompson, Chemistry, Class of 2020

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Baseer, Abdul A., Sofia Dildar, and Fareha Zafran. “The Use of Symbolic Language in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House: A Feministic Perspective.” Language in India 13, no. 3 (2013). http://www.languageinindia.com/march2013/baseer.pd

- Fuchs, Rachel and Victoria Thompson. Women in Nineteenth-Century Europe, 137-154 and 162-176. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- “Henrik Ibsen.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henrik_Ibsen (Accessed 13 April 2018).

- Ibsen, Henrik. A Doll’s House. Translated by William Archer. London: T. Fischer Unwin.

- Rekdal, Anne M. “The female jouissance: An analysis of Ibsen’s Et dukkenhjem.” Scandinavian Studies 74, no. 2 (2002): 149-180.

Images