Jeanne Deroin (1805-1894)

“We must make it absolutely clear that the abolition of the privileges of race, birth, caste, and fortune cannot be complete and radical unless the privilege of sex is totally abolished”

Jeanne Deroin (1805-1894) was a French seamstress, teacher, and journalist who argued passionately for the equality and emancipation of women and the working class. An early French socialist, she joined the followers of the utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon (1760-1825) in 1831. To support the struggle for the equality of working class women she founded several women’s journal, including La Femme Libre (The Free Woman) in the early 1830s

Jeanne Deroin was born in 1805 to a working-class family in Paris. She earned her living as a seamstress until 1834, when she earned her teaching license. Attracted to the Saint-Simonian views on the emancipation of women and socialism, Deroin began attending their meetings in 1831. Despite some severe reservations about marriage, Deroin married a fellow Saint-Simonian, Antoine Desroches, in a civil ceremony in 1832. Together they had three children

Deroin’s work as a journalist began with publications in the Saint-Simonian working women’s journal, La Femme Libre (The Free Woman), which she co-founded. Writing under the pseudonym Jeanne-Victoire she published articles arguing for marriage equality until the final issue in 1834. In the following years she earned a living as a teacher and brought up her children.

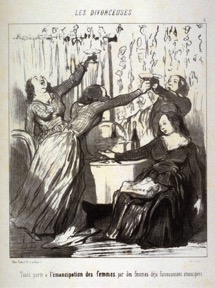

During the Revolution of 1848-49, Deroin took up the pen again and published articles and pamphlets on a number of social issues. These included the rights of women, child exploitation, the treatment of convicts, and the organization of labor. She contributed articles to the Voix des Femmes (Voice of Women) pertaining to women’s equality and founded the Société d’éducation mutuelle des femmes (Mutual Society for the Education of Women) with Desirée Gay (1810-1891), another early French socialist feminist. They published two issues of a political journal, named La Politique des femmes (The Politics of Women), but they could not sustain the journal financially. Afterwards, Deroin started a new journal titled Opinion des Femmes (Opinion of Women).

Beyond her prolific publications, Deroin attempted to run for office in 1849. She received fifteen votes and very little support from both her male democratic and socialist colleagues. Even some of her female contemporaries, such as the well know female novelist George Sand (1804-1876), considered her efforts futile without equal civil and political rights being established for women. Her willingness to campaign was representative of a radical ambition that manifested itself as L’Association Fraternelle et Solidaire de Toutes les Associations (The Fraternal and Solidary Association of Associations). This association aimed to combine a hundred existing worker’s associations into one conglomerate that would provide essential social services including education. After the defeat of the Revolutions of 1848-49, however, the right to assemble was revoked again. The offices of the L’Association Fraternelle et Solidaire de Toutes les Associations were raided and Deroin was arrested.

In prison she continued to write and petition the government. Upon her release she struggled to support herself and was eventually forced to flee to England to avoid re-arrest. After her emigration to London she lived in poverty with her two younger children. She tried to earn a living by writing and edited three women’s almanacs. Furthermore, she opened a school for the children of other exiles. This venture failed because of the low cost charged by Deroin for admittance. In the 1870s, she was eventually granted a 600 Franc pension by the French government. She continued to correspond with her French contemporaries into her eighties and was incorporated into William Morris’ Socialist League.

Jeanne Deroin spent her entire life advocating for the rights of women as equals of men and for the social equality of the working class. Despite all of her own personal struggles with poverty, imprisonment, and failure she continued to strive to improve the lives of the proletariat. In today’s society where women are still systematically disadvantaged compared to their male counterparts it is especially important to reflect and draw inspiration from history. Jeanne Deroin’s work emphasizes the importance of perseverance, even in the face of failure.

Lauren Overton, Chemistry and Neuroscience, Class of 2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Deroin, Jeanne, “Mission de la femme dans le present et dans l’avenir,” in Women, the Family, and Freedom, edited by Susan G. Bell and Karen M. Offen, 160. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983.

- Hauch, Gabriella, “Did Women have a Revolution? Gender Battles in the European Revolution of 1848/49.” In 1848: A European Revolution: International Ideas and National Memories of 1848, ed. Axel Körner, 64-81. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000).

- Moon, S. Joan. “Jeanne Deroin (1805-94),” Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolution, at: https://www.ohio.edu/chastain/dh/deroin.htm (Accessed 24 April 2018).

- Offen, Karen. European Feminisms 1700-1950: A Political History, 87-107. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Pamela Pilbeam, “Deroin, Jeanne,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/38771 (Accessed 24 April 2018).

Images