The New Woman

“As she mingles with the world, she feeds a kind of vanity by being mannish. To talk slang, to smoke cigarettes, to ride to hounds, commend her, in a measure, to her male companions. They declare her to be jolly, fetching stunning… but they rarely marry her” – Historian Patricia Marks

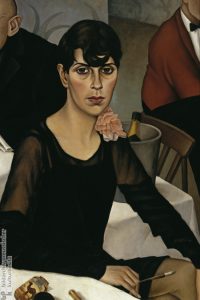

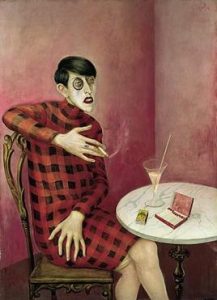

The “New Woman” emerged at the end of the nineteenth century as a woman characterized by attitudes and appearances typically associated with men. In the Interwar period the term “New Women” was used for the young and single wage-earning women that enjoyed the growing mass culture whit its movies and dance theaters, did sport, drove cars, if they could afford it and looked very different than the generation of their mothers. They cut their hair short to an Eton crop, wore short dresses, got rid of the corset used make up and smoked. These women are “oriented exclusively toward the present”, wrote Elsa Hermann, author of the 1929 book This is the New Woman, and “are fully capable of of satisfying the demands of their positions in life”. She was no longer concerned with being obedient to her parents or her husband and was more concerned with establishing her own means of independence through more education and more economic opportunities. An emphasis on financing her own lifestyle allowed this New Woman to further separate herself from the dominance of man.

This New Woman also began dressing more rationally by wearing less restrictive clothing that allowed more movement and literally liberated their bodies. This clothing allowed women to walk more easily, thus allowing women an opportunity to be out in public more and leave what historian Patricia Marks has described as “doll houses”, representative of the more conservative mindset which aimed to keep women in the home. These women continued to change their appearances with makeup, shorter dresses, and short hair, as demonstrated by the female flapper characteristic of the middle and upper-class woman during this time period. According to scholar Kenneth Yellis, a typical flapper “bobbed her hair, concealed her forehead, flattened her chest, hid her waist, dieted away her hips and kept her legs in plain sight”. With a new appearance that strayed away from strict social standards, women found they were able to further establish their own sense of independence.

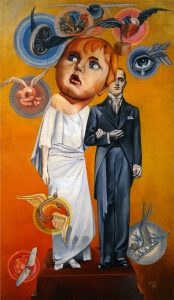

This New Woman however drew some criticism from society for her perceived threat to the family structure. While women were traditionally expected to stay home and be the perfect mother, the New Woman strayed away from this ideal and instead chose to pursue the life she wished to live. More conservative members of society found this shift to be a threat to modernization, as upper class and middle-class women were supposedly abandoning their obligations of caring for their family. Women that chose to embrace the lifestyle associated with the New Woman were seen as, according to Yellis, “brazen and at least capable of sin if not actually guilty of it”. These mysterious and scandalous attitudes associated with these women were threatening to a worldview in which women were to remain at home and rely on their husbands.

The concept of the New Woman and its emphasis during the Interwar period revitalized and reinvented what it meant to be a woman. Upper class women not only experienced economic freedoms, but also sexual freedoms as women began finding the strength to expand their world view. Women now found that they had more of a choice in their daily lives and were thus able to change the dynamics of personal female liberties. Remembering this transitional period for women’s roles remains relevant and even essential. The expanded freedoms of the New Woman- as well as the never-ending process of re-defining gender roles- remains with us today.

Olivia Porter, Global Studies, Class of 2020

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Hermann, Elsa, “This is the New Woman.” In Lives and Voices: Sources in European Women’s History, ed. Lisa DiCaprio and Merry E. Wiesner, 455-457, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, New York.

- Marks, Patricia, Bicycles, Bangs, and Bloomers: The New Woman in the Popular Press. Lexington: University of Kentucky, 1990.

- Yellis, Kenneth, “Prosperity’s Child: Some Thoughts on the Flapper”, American Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1969): 44-64.

Images