Women’s Suffrage Society (Société le suffrage des femmes) (1876-1909)

“As long as we remain excluded from civic life, men will attend to their own interests rather than ours.” – Women’s Suffrage Society

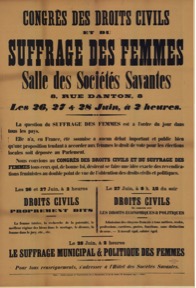

The Women’s Suffrage Society (Société le suffrage des femmes, SFF) became France’s first women’s suffrage group. Its founder, Hubertine Auclert (1848-1914), was a feminist who believed in equal civil rights and suffrage rights for women. She fought her whole live for the representation of women in French politics. In 1876 she founded the society for the Rights of Women (Société le droit des femmes) that supported equal women’s suffrage; 1883, the organization formally changed its name to Women’s Suffrage Society (Société le suffrage des femmes), which was popular in more liberal and socialist circles across the country, but did not gain large national following, because of its militant strategy. The French Suffrage Society was followed by the French Union for Women’s Suffrage (Union française pour le suffrage des femmes, UFSF), established in 1909, which was more moderate in strategy and tactics.

The militant strategy of the French Women’s Suffrage Society was marked by symbolic public actions and civil disobedience. One example for this militancy is an action in 1904, in which Auclert other women publicly burned the patriarchal Code Napoléon, the French civil code established under Napoléon I in 1804, which gave women no equal rights in family and marriage. Like this example, most of the group’s acts were not violent towards people, but instead towards significant objects they saw as symbolic of the oppression of women. Only a minority in the French Women’s Suffrage Society executed acts of symbolic violence or destruction, but thousands participated during their protests and marches for a more equal French society. The members of the Women’s Suffrage Society were mostly from the middle class. Very view aristocratic and upper-class as well as proletarian women were involved.

The supporters of the French Women’s Suffrage Society believed a rhetoric long held by its leader Hubertine Auclert: that the main reason women had not seen a change in their rights was that there were no women in the parliaments and other positions of power to support their demands. In addition, most men saw, accruing to Auclert, no incentive to include women in politics, because they feared it would reduce their standing. Auclerts main argument for the necessity of women to be allowed to vote and holding elected office was that men, who were not personally affected negatively by women’s inequality of rights, or even gained by it, had no reason to support women’s causes.

In 1900 the Women’s Suffrage Society supported the foundation of the National Council of French Women (Conseil National des femmes françaises, CNFF). The CNFF served as an umbrella organization for the middle- and upper-class women’s movement in France.

Despite the efforts of the French Women’s Suffrage Society and the UFSF, that followed, France didn’t grant women’s suffrage until 1944, much later than many other European countries. Historically, France led the way for progressive thought and political revolutions. However, it is likely that women’s suffrage took longer for this very reason. French lawmakers feared that French society was not equipped to handle women’s suffrage and the changes it would bring in politics. The Conservatives believed that politics was a “men’s matter,” the Liberals and Republicans worried that women would vote mainly for the conservative parties, because they were more religious than men.

The militant Women’s Suffrage Society is still important today because it was the first of its kind in France, even though more moderate and influential groups followed. Similar to the members of the Women’s Social and Political Union in Britain, founded in 1904, the members of the French Women’s Suffrage Society resorted to militancy, because they felt that this was, after a long-term struggle to make their voice heard. the only way to create more public attention. Auclert and other women were intelligent, tactical people and felt that physical actions sent a stronger message than just meeting, marching or demonstrating.

Grayson Holmes, History and Philosophy, Class of 2020

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “France Marks 70 years of Women’s voting rights.” France 24, at: http://www.france24.com/en/20140421-france-womens-voting-right-anniversary (Accessed: April 15, 2018.).

- Eichner, Carolyn J. La Citoyenne in the World: Hubertine Auclert and Feminist Imperialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009.

- Hause, Steven and Kenney Anne. “The Limits of Suffragist Behavior: Legalism and Militancy in France, 1876-1922.” American Historical Review. 86, no. 4 (1981): 781-806.

- Nuñez, Rachel. “Rethinking Universalism: Olympe audouard, Hubertine Auclert, and the Gender Politics of the Civilizing Mission.,” French Politics. Culture & Society 30, no. 1 (2012): 23-45.