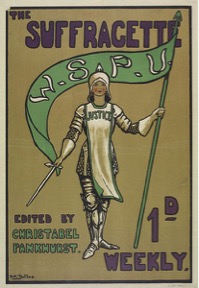

Vote for Women / The Suffragette / Britannia (1907-1918)

“Votes for Women!” – Slogan of the Women’s Social and Political Union

The Suffragette was since 1912 the newspaper of the British Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU); it replaced the previous journal of the organization, Vote for Women. Referred to as the “official organ” of the WSPU, it was the organization’s main platform for relaying their beliefs and philosophy to the public. Over the course of its 271 published issues, the newspaper changed along with the organization.

The first newspaper of the WSPU was Votes for Women, founded in 1907 by Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. It was first published monthly, but soon after Pethick-Lawrences decided to start publishing the newspaper every week. The editors also stopped trying to make a profit off it its sales and reduced the price, which suggests that they were more interested in the dissemination of their ideas than monetary gain. In 1912, Christabel Pankhurst (1880-1958), one of the co-founders of WSPU, told the Pethick-Lawrences of her plans to include arson in the militant strategies of the suffragette movement. When they objected to the arson campaign, Pankhurst dismissed them from WSPU and they lost control of their newspaper. Thus, The Suffragette became the new publication for WSPU, edited by Pankhurst. This newspaper did not do quite as well as Votes for Women. While Votes for Women had circulation of 30,000 per week, the Suffragette circulated only around 17,000 copies per week at its peak. The paper’s lack of success was due in part to the arrests of essential publishers and governmental suppression of the newspaper. In 1913, the managing director of the printing company was arrested. Later, Pankhurst fled to France to avoid arrest, which left Annie Kenney (1879-1953), an English working-class suffragette who became a leading figure in the WSPU. in charge of the The Suffragette. Attempts by authorities to weaken the newspaper lowered the circulation to around 10,000 copies per week. The paper’s success declined in conjunction with the decreased support for WSPU and militancy within the suffrage movement. When the Pethick-Lawrences left the WSPU with their newspaper, this led to a bigger split within the women’s suffrage movement as a whole. Many were unwilling to accept the radical actions of the militant suffragists.

The Suffragette was not the final name of the WSPU newspaper. In 1914, when Britain went to war with Germany, this prompted the WSPU to negotiate with the British government. Authorities agreed to release all imprisoned suffragettes if the WSPU would stop their militant activities and advocate for support of the war. Because of this agreement, the WSPU renamed their newspaper Britannia. This newspaper, as the main platform of the WSPU, advocated to pause the campaign for women’s suffrage and instead offer total support of the war. Yet, the newspaper Britannia faced even more raids by police than The Suffragette due to the government’s attack on its leaders. Due to so many raids, the newspaper team had to set up their own printing press. Britannia produced its final copy on December 20, 1918, after the British government passed the Representation of the People Act of 1918, giving all men and women over the age of thirty the right to vote.

This newspaper, through all of its transitions, was vital to the British women’s suffrage movement. It was the platform that allowed the WSPU’s ideas to reach the general public of Britain and pushed the movement forward. Nevertheless, the newspaper also provides an illustrative example of how divided members of the women’s suffrage movement were on issues of strategy. Regardless of the division within the movement or the opposition the movement faced, the newspaper was essential in the relay of ideas that helped women gain the right to vote.

Shana Loudermelk, History and Psychology, Class of 2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “Christabel Pankhurst.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Christabel_Pankhurst&oldid=828135017 (Accessed April 22, 2018).

- “The Suffragette in British Newspaper Archive.” https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles/the-suffragette (Accessed April 22, 2018).

- “The Suffragette Newspaper – IET Archives Blog,” at: https://ietarchivesblog.org/2017/10/19/the-suffragette-newspaper/. (Accessed April 22, 2018).

- “Women’s Social and Political Union.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Women%27s_Social_and_Political_Union&oldid=836170801. (Accessed April 22, 2018).

- “Women’s Suffrage in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_suffrage_in_the_United_Kingdom. (Accessed April 22, 2018).

- Simkin, John. “Suffragette.” Spartacus Educational, August 2014. http://spartacus-educational.com/WsuffragetteJ.htm.

- Simkin, John. “Votes for Women.” Spartacus Educational, August 2014. http://spartacus-educational.com/WvotesM.htm (Accessed April 22, 2018).

Images