August Bebel (1840-1913) and his book Woman and Socialism (1879)

“There is no liberation of humanity without social independence and gender equality”

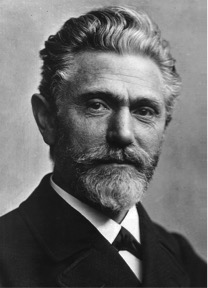

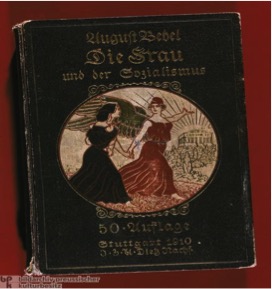

August Bebel (1840-1913) was one of the most influential leaders of German and international socialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, who fought for social justice and women’s liberation. Bebel’s 1879 book, Die Frau und der Sozialismus (Woman and Socialism), provided a programmatic platform for the socialist women’s movement. Between 1879 and 1914, the year of the beginning or World War I, Woman and Socialism came out in over fifty edition and had been translated into over twenty different languages. The first English edition was published in 1908. Unlike many of his fellow male comrades in the labor movement, Bebel believed that women are equals to men and should have the same economic, social and political rights and duties.

Ferdinand August Bebel was born in February 1840, in Deutz, Germany, now part of Cologne. He was the son of a Prussian non-commissioned officer in the Prussian infantry, and was born in military barracks. Wilhelmine Johanna Bebel, August Bebel’s mother, struggled to financially support her family after the death of both of her husbands. Bebel’s formal education was cut short at the age of 14 after he was offered an apprenticeship as a carpenter and wood worker. Similar to most educated German workmen in the mid-nineteenth century, Bebel traveled extensively in search of work after he had finished his apprenticeship, obtaining a first-hand knowledge of the economic and social difficulties working-class people faced from day to day.

After being rejected from voluntary military service, Bebel moved back to Leipzig to work as a master turner, making horn buttons. Upon his move to Leipzig in 1861, Bebel became interested in politics and joined the Leipzig Workers Educational Association, one of the many self-help groups that formed during the 1850s and 1860s. Groups like the Leipzig Workers Education Association were usually formed and lead by liberal, reform-oriented middle-class leaders and focused on helping working class men to develop a core knowledge of social issues as well as practical skills to discuss those issues, such as public speaking. Radical working-class members of these groups challenged the apolitical nature, intended by the leaders, and made them a place of intense discussion and controversy. They “were intent on jettisoning the educational focus for a real involvement in political matters, a transformation that Bebel resisted at first.” Bebel was originally an opponent of socialism but was increasingly drawn into the labor movement after reading pamphlets written by Ferdinand Lasalle (1825-1864). He was a German-Jewish jurist, philosopher and socialist, who initiated the Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein (General German Workers’ Associationor ADAV) in 1863, which popularized Marxist ideas. Bebel was attracted to Marxism because it gave him hope for a change to the better. However, it wasn’t until he came under the influence of Wilhelm Liebknecht (1826-1900), who was also a leader of the ADAV, but more radical than Lasalle, that he became fully committed to the Marxist cause.

In 1867 August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht founded together the Sächsische Volkspartei (Saxon People’s Party) and two years later in 1869 Eisenach the Socieldemocratic Workers Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands. SAPD), which merged with the ADAV. In addition to his strong oratorical power, Bebel’s ability to organize speeches, rallies and protests made him widely popular among both, the members of the SAPD and the trade unions. The influence of the SDAP was quickly growing the in newly founded German Empire of 1871, indicated by the election for the Reichstag, the national parliament, which were based on universal male suffrage. Bebel and Liebknecht were elected in the Reichstag too.

In order to repress the growing popularity of socialist ideology the German government implemented the Anti-Socialist Laws, in 1878, which were in place until 1890. These laws banned all socialist groups, meetings and publications and led to the persecution and imprisonment of many of its leaders, members and supporters. During the 1870s and 1880s, Bebel was imprisoned for a total of four and a half years for insulting the monarch, distributing unapproved leaflets, denouncing militarism and treason. However, the Anti-Socialist Laws allowed socialist to run for office, including Bebel. Contrary to the aims of the German government, the repressive nature of the Anti-Socialist Laws did not weaken German socialism. In fact, by 1890, the SPD, which had been officially re-founded as the Social Democratic Party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschland, SPD) had doubled in size and polled 20 percent of the electorate in the Reichstag elections. Additionally, another loophole in the laws allowed candidates to run for election in multiple districts, therefore Bebel was often a candidate in multiple districts.

While imprisoned because of the Anti-Socialist Laws, Bebel wrote Woman and Socialism, a book discussing the plights of women from economic, political, social and psychological perspectives. In 1879 Woman and Socialism was published and became the most educational text for working class women. One of the most notable points in Bebel’s book is his argument that the domination of women by men is rooted in history, not biology. The book had a major impact on working-class women, not only had someone finally written about them, but the person that wrote about them was one of the two leaders of German socialism. Woman and Socialism paved the way to the involvement in the socialist movement for many workers’ wives and women workers as well as for women from bourgeois and petit-bourgeois strata. In Woman and Socialism, Bebel explains that women were doubly disadvantaged in capitalist society: women suffered both “from social and societal dependence on the men’s world,” and from the “economic dependence in which women in general and proletarian women in particular find themselves together with the proletarian men.” Bebel argued that a successful struggle for the occupational, juridical and political equality might moderate this double oppression but could never fully eliminate it. A solution for the “women’s question” was only possible with the overall “removal of social antagonisms” from the societal framework. For Bebel, once the “social question” as a whole had been solved and the capitalist economic and social system had been dislodged, “sexual slavery” would finally disappear.

In Woman and Socialism, Bebel voiced his support for a wide array of feminist demands, such as the active and passive universal suffrage for men and women on all levels, the right to equal education and enter universities, practice professions and the right for married women to own their own property and to initiate divorce proceedings. However, Bebel’s demands for women’s rights to dress freely and to have sexual satisfaction were seen as outlandish. In fact, many of his demands were seen as extreme and extended past the beliefs of most feminists of the day. Woman and Socialism offered a more distinct view of the socialist future, suggesting directions for action and pointed to methods by which proletarian women could free themselves from their unsatisfactory position.

Woman and Socialism was a foundational text for both the labor movement and the socialist women’s movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Bebel’s book inspired socialist feminist leaders such as Clara Zetkin (1857-1933) and energized working class women to take an active role in the fight for women’s rights.

August Bebel remained the leader of the SPD until his death in 1913. He was regularly elected in the Reichtags, where he criticized the politics of the German Emperor, its government and the conservative majority in the Reichstags for its imperialism, militarism and support of capitalist exploitation of the workers in several speeches. He also argued in the Reichstag against the patriarchal Civil Code (the Bürgerliche Gesetzbuch, BGB) of 1900 and its suppression of female autonomy. By 1912, one year before Bebel’s death, the SPD reached 35 percent of all male voters in the Reichtag elections and became the largest and most successful political organization in Germany, which since 1891 also had allowed women to form their own organization inside the SPD. In the Novemberrevolution 1918 that ended the First World War in Germany, forced the Emperor into exile and created the Weimar Republic, German women finally got the right to vote. Bebel and the SPD were the first to demand this right for women.

Kaitlyn Capps, Majors in Political Science and Global Studies, Class of2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Frevert, Ute. “Women Workers, Workers’ Wives, and Social Democracy in Imperial Germany.” In Bernstein to Brandt: A Short History of German Social Democracy, edited by Roger Fletcher, 34-44. London: Edward Arnold, 1987.

- Sowerwine, Charles. “Socialism, Feminism, and the Socialist Women’s Movement from the French Revolution to World War II.” In Becoming Visible: Women in European History, ed. Renate Bridenthal, Susan M. Stuard, and Merry E. Wiesner, 367-369. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

- Roth, Gary. “Bebel, August.” In Encyclopedia of Modern Political Thought, ed. Gregory Claeys, 69-72. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Ltd., 2013.

- “August Bebel.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/August_Bebel (Accessed 19 April 2018).

Images