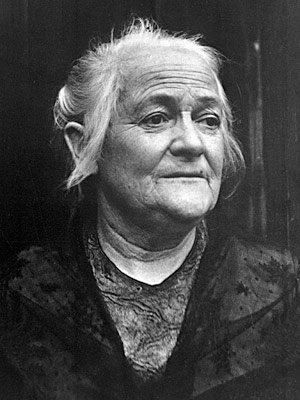

Clara Zetkin (1857-1933)

“Workers must rather get accustomed to treat female laborers primarily as female proletarians, as working-class comrades and as equal and indispensable co-fighters in the class struggle”

With her struggle for working class women’s emancipation, Clara Zetkin (1857-1933) became one of the most important leaders of the socialist women’s movement in late nineteenth century and early twentieth century Germany. She and her contemporaries began to approach women’s emancipation not just as in issue of women’s rights, but also as a socioeconomic issue that demanded political and economic reforms for women and men alike.

Clara Zetkin (née Eissner) was born in July 1857 in Wiederau, Saxony, Her father was a schoolmaster and her mother was born to a well-educated middle-class family from Leipzig. Zetkin studied to be a teacher at the Leipzig Teacher’s College for Women. Perhaps influenced by her upbringing and social class, it was during her time there that she became involved with the women’s movement and the in 1878 she joined the Socialist Workers’ Party (SAP), which changes its name to Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in 1890.

In 1878, German chancellor Otto von Bismarck banned all SPD activity in an attempt to curb the party’s power in the government. Following this act, Zetkin and other leading members of the SPD had to leave Germany to avoid persecution and prison. Zetkin migrated first to Zurich, and then to Paris. While in exile, she met her partner Ossip Zetkin. Though they never married, she took his name and together they had two sons. When the Anti-Socialist Law was finally lifted in 1890 Zetkin returned to Germany to live in Stuttgart. She joined the newly founded SPD.

Zetkin became the leading female theorist of socialist emancipation theory and as such helped to formulate the core ideas of socialist feminism. An important medium for her to spread socialist ideas in circles of working class was the socialist women’s journal of the SPD, Die Gleichheit (Equality), which Zetkin edited until 1917. Here, and elsewhere she argued that women could only become emancipated if they worked like men and earn their own income, which would made them independent from men and integrated them in society and politics. They should receive the same pay and privileges as men in the workplace. For her wage inequality hurt women and men. She strongly made this arguments in an article in Die Gleichheit published in December 1893, in which she addressed this issue. The article served as a call to action. It framed women’s economic equality and social emancipation as a matter of class struggle between bourgeoisie and proletariat, only after a socialist revolution women could really become equal as women and as workers. Zetkin argued that wage inequality would hurt both, female workers because the poor wages made it incredibly difficult for women to afford adequate living conditions, and male workers because of the competition of cheap female labor. As a result, Zetkin called equal wages and stronger attempts pf the SPD and the trade unions to organize women in the labor movement. Only when women became equal to men at work and, by extension, in the home could they begin working towards class reforms. In addition to promoting socialist feminism, Zetkin provided some much-needed leadership and structure in the German socialist women’s movement.

During the First World War, Zetkin, along with Karl Liebknecht (1871-1919) and her friend Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919), belonged to the small opposition in the SPD that rejected the party’s policy of Burgfrieden (a truce with the government, promising to refrain from any strikes during the war). Among other anti-war activities, Zetkin organized an International Socialist Women’s Conference against the war in Bern, in neutral Switzerland, from March 25-28, 1915, to which all other participants had to travel illegally. Despite the danger of imprisonment, 25 women from, Britain, France Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Russia and Switzerland participated in this first international women’s conference for peace, which ended with a joint resolution. Because of her anti-war opinions, Zetkin was arrested several times during the war, and in 1916 taken into “protective custody” (from which she was later released on account of illness).

In 1916 Zetkin was one of the co-founders of the Spartacist League (Spartakusbund), which published illegal, anti-war pamphlets pseudonymously signed “Spartacus” (after the slave-liberating gladiator who had opposed the Romans). The Spartacus League vehemently rejected the SPD’s war policy and supported the growing number of riots and strikes against the war all over Germany. In April 1917 Zetkin joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) which had split off from the SPD, in protest at its pro-war stance. In January 1919, after the German Revolution in November 1918 she became a co-founder of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), for which she was elected in the Reichstag, the parliament of the newly founded Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1933.

Until 1924, Zetkin was a member of the KPD’s central office and from 1927 to 1929 she was a member of the party’s central committee. She was also a member of the executive committee of the Communist International (Comintern) from 1921 to 1933. In 1925 she was elected president of the German left-wing solidarity organization Rote Hilfe (Red Help). In August 1932, as the chairwoman of the Reichstag by seniority, she was entitled to give the opening address, and used it to call for workers to unite in the struggle against fascism. After Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party took over power in January 1933, the KPD was banned. Zetkin went into exile to the Soviet Union. She died there, near Moscow, in 1933, aged nearly 76.

Although she passed 85 years ago, Clara Zetkin remains an invaluable fixture in modern feminist movements. Even now, women are still fighting for equal pay in the workplace, and figures such as Zetkin remind modern women that cooperation is of utmost importance, and that perseverance is critical to making progress in the movement for women’s equality. Zetkin’s most lasting legacy however, is her reputation as an organizer and effective leader. It’s no secret that modern politics and social movements are deeply affected by partisanship, so Zetkin is most relevant in that she is an example of what can be achieved with organization and cooperation.

Nicole Sotelo, History and Political Science, Class of 2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Frevert, Ute. “Women Workers, Workers’ Wives, and Social Democracy in Imperial Germany.” In Bernstein to Brandt: A Short History of German Social Democracy, ed. Roger Fletcher, 34-44. London: Edward Arnold, 1987.

- Simkin, John. “Clara Zetkin.” Spartacus Educational, at http://spartacus-educational.com/GERzetkin.htm (Accessed April 13, 2018).

- Sowerwine, Charles. “Socialism, Feminism, and the Socialist Women’s Movement from the French Revolution to World War II.” In Becoming Visible: Women in European History, ed. Renate Bridenthal, Susan M. Stuard, and Merry E. Wiesner, 357-387. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

- “Zetkin, Clara .” Oxford Reference, at: http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195148909.001.0001/acref-9780195148909-e-1190 (Accessed April 13, 2018).

- Zetkin, Clara. “Women’s Work and the Organization of the Trade Unions,” Die Gleichheit, 1 November 1893. In Lives and Voices: Sources in European Women’s History, ed. Lisa Caprio and Merry E. Wiesner, 371-376. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Images

Clara Zetkin, c. 1908.

Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg, 1910

Clara Zetkin, c. 1932