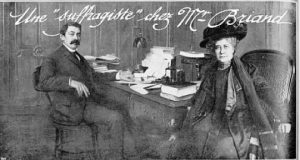

Jeanne Schmahl (1846-1915)

“Taking into consideration that the Civil Code is the one great obstacle to the emancipation of women in France, we decided to attack it”

Jeanne Schmahl (1846-1915) was one of the most influential early leaders of the French middle- and upper-class women’s movement between the 1860s and 1910s. In 1893 she founded the l’Avant-Courrière (Forerunner) association in 1893, which fought for equal civil rights of women in marriage and family and in 1908 founded the French Union for Women’s Suffrage (Union française pour le suffrage des femmes, UFSF) to campaign for the right of women to vote. Schmahl’s impact on the lives of French women are exhibited in her drive to implement changes in the oppressive nature of female-focused laws and can still be seen in today’s modern society.

Jeanne Schmahl, born as Jeanne Elizabeth Archer in Great Britain in 1846, was a child of a lieutenant in the British Navy and his French wife. The parents gave her a good education and Schmahl was able to begin the study of medicine in Edinburgh during the wake of Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912)—who went on to become Scotland’s first practicing female doctor and advocator for female education in medicine. She moved to Paris to continue her study there, but never got a degree. Instead, she practiced as a midwife until marrying, Henri Schmahl, a wealthy French businessman from Alsace in 1873. The marriage made her a French citizen.

In 1878 Jeanne Schmahl joined the League for Raising Public Morality (Ligue pour le relèvement de la moralité publique), which was mainly concerned with making alcohol and pornography illegal. Increasingly she became active for women’s rights issues too. The first women’s rights organization she joined was the Society for the Amelioration of Woman’s Condition (Société pour la Revendication du Droit des Femmes ), which had been created by Maria Deraismes (1828-1894) in 1866.

Schmahl admired the British Married Women’s Property Act 1882 and she believed a similar law would benefit French women, thus the struggle for equal civil rights and marriage and family for women became her first main aim. One motivation for this struggle was the case of a woman, reported in the press, who had been dismissed by her employer for asking not to give her earned wages to her alcoholic husband. The common practice in France was indeed that the wage a woman earned, was given to her father or husband. For Schmahl this issues was not only of importance for equal female property rights, but also for the advancement of women, because she believed that financial freedom was the root of all liberty. Therefore, Schmahl directed all her efforts now on this issue and founded in the l’Avant-Courrière (Forerunner) association in 1893, which called for the right of women to be witnesses in public and private acts, and for the right of married women to take the product of their labor and dispose of it freely. In 1895 Jeanne Schmahl wrote:

Taking into consideration that the Civil Code is the one great obstacle to the emancipation of women in France, we decided to attack it. Not, however, in its entirety, as had previously been attempted, but piecemeal, beginning by what appeared to be least defended by our opponents and therefore easiest of conquest; at the same time choosing the point which should logically come first, as the foundation of women’s freedom. We were not long in coming to the conclusion that, financial freedom being the root of all liberty, we must first set to work to obtain for married women the right to their own earnings.

Finally, in 1896 the French Chamber of Deputies passed the Married Woman’s Earnings Act, but it was not until July 1907 that the Senate would reciprocate. in 1907, the Earnings Act was implemented, often called the “Schmahl Law.” It allowed for women to be in possession of their own earnings, however, while it did provide a woman financial freedom, property rights based on items that were not consumed by her were still a concern and never addressed until later.

Schmahl used the ratification of the Married Woman’s Earnings Act, which made her to one of the most influential French women in her time, to push now for another matter: equal suffrage rights for women. She founded together with others the French Union for Women’s Suffrage (Union française pour le suffrage des femmes, UFSF) in 1908, which started to work in 1909 for equal universal suffrage for women. While men’s universal suffrage was formally ratified during the Revolution of 1848 in France, French women were excluded from this right (until 1944). The UFSF argued that as women deserved the equal right to vote, because they were working in increasing numbers in in the economy and were having a responsibility for the future of their children and family. Jeanne Schmahl became the first president of the UFSF, but had to resign from this position because of her deteriorating health in 1911. She died in 1915. Her obituary said,

Mme. Jeanne Schmahl was before her day—a pioneer who did not claim to be a prophetess. She reasoned and persuaded… It was her deliberate intention and in kindness of heart that she wished to improve us [men] by improving the condition of women… She kept her foot on solid earth. She did not forget reality—that was her strength; that and the gentle but firm obstinacy with which she cultivated her garden.

Neither her bourgeois background, nor her marriage to a well-off husband, could stop Jeanne Schmahl to fight in the French women’s and suffrage movement. Her dedication to the advancement of women was important in France and allowed women of all classes to become active members of society and politics.

Francisco Nguyen, Psychology, Class of 2018

Sources

Literature and Websites

- “French Union for Women’s Suffrage.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Union_for_Women%27s_Suffrage (Accesses, 21 April 2018).

- “Jeanne Schmahl.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeanne_Schmahl (Accesses, 21 April 2018).

- “Married Women’s Property Act 1882.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Married_Women%27s_Property_Act_1882 (Accesses, 21 April 2018).

- Bell, Susan Groag., and Karen M. Offen. Women, the Family, and Freedom: The Debate in Documents, 98. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983.

- Schmahl, Jeanne E. “Progress of the Women’s Rights Movement In France.” Forum (September 1896): 79. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/90914913?accountid=14244.

- Schmahl, Jeanne. “The French Union for Women’s Suffrage: ‘The Question of the Vote for Women’.” In Lives and Voices: Sources in European Women’s History, ed. Lisa Caprio and Merry E. Wiesner, 385-386. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Images