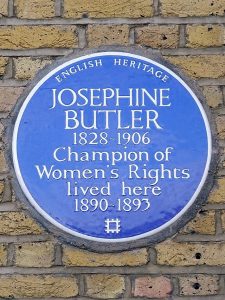

Josephine Butler (1828-1906)

“There is much more exact correspondence between the natural and moral world than we are apt to take notice of”

Josephine Elizabeth Butler (1828-1906) was a Victorian feminist and social reformer who campaigned for women’s suffrage, the right of women to better education, the end of coverture in British law, the abolition of child prostitution, and an end to human trafficking of young women and children into prostitution.

She was born in April 1828 in Milfield, Northumberland into a wealthy and rather prominent family as the fourth daughter and seventh child of Hannah (née Annett) and John Grey, a land agent and agricultural expert. In 1833 John Grey was appointed manager of the Greenwich Hospital Estates in Dilston, near Corbridge, Northumberland, and the family moved to the area. Her father treated his children equally within the home. He educated them in politics and social issues and exposed them to various politically important visitors. John Grey’s political work and ideology had a strong influence on his daughter, as did the religious teaching she received from her mother.

In October 1852, Josephine Elizabeth Grey married George Butler, a Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford. George was a scholar and cleric and shared with his wife a commitment to liberal reforms and a love of Italian culture. In 1852 the Butlers had their first son, George Grey Butler, followed by a second, Arthur Stanley in My 1854. Their third son, Charles, was born in 1857. In 1859 Butler gave birth to her last child, a daughter, Evangeline Mary. The parents lost two of their four children, Arthur and Eva, in young age. Because of the deteriorating health Josephine Butler the couple moved from Oxford to Clifton, near Bristol, in 1856 ten years later to Liverpool, where George Butler was appointed headmaster of Liverpool College.

In Liverpool, the Butler continued the social work they had jointly started before in Clifton: To provide shelter in their own home for some of the homeless women in the city, often prostitutes in the terminal stages of a venereal disease. It soon became clear that there were more women in need than they could provide for, so Butler set up a hostel, with funds from local men and women of means; more followed in other cities. In 1869, Butler began her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts of 1866 and 1869. These had been introduced by the government in an attempt to reduce venereal disease in the armed forces. Police were permitted to arrest women living in seaports and military towns who they believed were prostitutes and force them to be examined for venereal disease. Butler toured the country making speeches condemning the acts. Many people were shocked that a woman would speak in public about sexual matters. Essentially, Butler was seen as an ally to sex workers, as she recognized the double standard as men’s right to sexual access to women and children, while those same women and children were considered outcasts. Her struggle had success, in 1883 the Contagious Diseases Acts were suspended, but repealed three years later. She also achieved that the age of consent for marriage was increased from 13 to 16 years.

To support the struggle for the abolition of state regulation of prostitution and the fight against international trafficking of women into prostitution in a more organized international manner, Butler helped to found in 1875 the International Abolitionist Federation (IAF) in Liverpool, originally called the British and Continental Federation for the Abolition of Prostitution. The IAF was active in Europe, the Americas, and the European colonies and mandated territories. It argued that state regulations encouraged prostitution while having the effect of enslaving women in prostitution. For the IAF the solution lay in moral education, empowerment of women through the right education and properly paid work, and marriage.

Parallel to all her activities and travel, Butler wrote and published for her cause. Newspaper articles and essays. In 1896, her most famous work Personal Reminiscences of a Great Crusade, appeared, which much like her other publications, promoted social reform, women’s education and equality.

Josephine Butler’s work is still relevant today, in terms of the debate within the feminist community in regards to sex work. As a feminist, I think it is important to be an ally to sex workers and to recognize them within the feminist movement. Often times, they are ignored or spoken for when in fact, no one knows what needs to be done in their favor, better than them. Furthermore, Butler advocated and assisted these women in a time when women couldn’t vote and it was extremely rare to even see a woman of status talk about sex, let alone sex work, therefore, we have more power today than Butler did when she worked to influence her own society. I think we should follow Butler’s footsteps and strive to create a safe place for these women and use our power to vote and speak for “outcasts” everywhere.

Alyssa Atwell, Quantitative Biology & Women and Gender Studies double major, Medical Anthropology minor, Class of 2020

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Fawcett, Millicent Garrett, and E. M. Turner. Josephine Butler: Her Work and Principles and Their Meaning for the Twentieth Century. London: Association for Moral & Social Hygiene, 1927.

- “Josephine Butler (1828-1906).” BBC History, at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/butler_josephine.shtml (Accessed April 25, 2018).

- “Josephine Butler.” Wikipedia, at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josephine_Butler (Accessed April 25, 2018).

- Jones, Claire. “Josephine Butler 1828-1906.” HerStoria, at: https://herstoria.com/josephine-butler-1828-1906/ (Accessed April 25, 2018).

- Mathers, Helen. Patron Saint of Prostitutes: Josephine Butler and a Victorian Scandal. Stroud, Gloucestershire: History Press, 2014.