Social Democratic Women’s Movement in Germany (1891-1914)

“The workers must rather get accustomed to treat female laborers primarily as female proletarians, as working-class comrades fighting class slavery and as equal and indispensable co-fighters in the class struggle” – Clara Zetkin

The rise of social democratic women’s movements was the product of several related dynamics in late nineteenth century German society. One important factor was industrialization. More and more working class women entered the industrial workforce, but employers paid women significantly less wages than male workers. Female workers often worked long hours in horrible working conditions, with unsanitary workplaces, no bathroom breaks, and no machinery training.

The spread of Enlightenment ideas such as social, civil, and political equality of men and women also encouraged the development of social women’s organizations. One of the major proponents of socialism was August Bebel (1840-1913), the leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) before 1914. He came from a poor working-class family and learned the craft of a wood turner. He understood and supported women’s liberalization as an important part of the socialist movement. His book Women and Socialism, published first in 1879, became the bestseller for working class women of their time and inspired them to get involved into politics.

After the Anti-Socialist Law of Imperial Germany was lifted in 1890, which had been implemented in 1878, the SPD was re-founded, but women were not allowed to become members because of laws that prohibited their political organization until 1908. For this reason, the SPD created an independent women’s organization in 1891, which worked very successful until 1908, when women were allowed to become members of the SPD and any other political party. The existence of a separate organization created a space for women to develop their political skills, which helped to recruit many women.

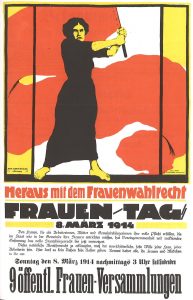

In 1908, despite the new legal situation, therefore the female SPD leaders, Clara Zetkin (1857-1933), Luise Zietz (1865-1922), and Ottilie Baader (1847-1925) and others, felt that women still needed separate organization, not at least because of the continuation of gender hierarchies within the party. In response, the SPD decided to require that all local branches have one woman on the executive board, and established a women’s bureau (which was subordinate to the national party executive board). The social democratic women’s movement continued to flourish and transformed into a mass movement. In 1906, the SPD had 6,460 female members, by 1910 it had reached 82,642 female members.

Parallel to the growth of the female membership of the social democratic party, the number of women members in the Free Trade Unions also dramatically increased. In 1900, the number of female unionists was 22,844. By 1906, the number of women in trade unions had increased to 118,908. Reflecting the increase in female trade union members, the social democratic women’s organization constituted itself as a movement of female workers and defined women’s gainful employment as the most important condition of women’s emancipation. However, it included housewives as well.

An effective method for the social democratic women to share their views with its female and male supporters was the SPD women’s magazine Die Gleichheit (Equality), edited by Clara Zetkin. In 1910, it reached a circulation of 80,000, which further increased to 124,000 until 1914. One of the regular supplement the newspaper published was dedicated to women as housewives and mother, another was dedicated to children.

The separation of women’s organization from the main party was a key to the success of the social democratic women’s movement in p-1914 Germany, which became the largest and most radical socialist women’s movement in Europe. It integrated mainly working-class women in its ranks, providing them with the knowledge to empower themselves and strive for equality among the ranks of men in the SPD and society. Although some middle-class women became active in the social democratic women’s movement, the organization distanced itself from the bourgeois women’s movement, represented by the Federation of German Women’s Associations (BDF) founded in 1893, and vice versa, because of their differing class interests and political views. Only occasionally and on the local level SPD and BDF women worked together before 1914, mainly in municipal welfare activities.

The SPD taught working-class women independence and self-respect by giving them a voice of their own. The organization not only empowered working-class women to demand equality, but it also provided a strategy for women in the workforce to strive for economic freedom, demand better working conditions, and push for the equal pay of men and women. The social democratic women’s movement provided women with a space where they could speak freely and feel secure without the disapproval and ridicule of men. Women were given a political platform to speak about the issues affected their lives.

The steadfastness and organized work that the social democratic women in Germany did set the foundation for the equality of women not only in Germany, but in other nations as well. Many of the feminists today demand equality and justice between the sexes as it relates to wages in different professions, representation of women in male-dominated jobs (i.e. politics), and sexual harassment within the workplace. There are several issues that remain a problem in society that women and men are fighting to solve. Some of the demands that the social democratic women made in Germany during the nineteenth century are similar, if not the same, as those that we are currently facing in the 21st century.

Leeza Mason, Biology Major, Chemistry and History Minors, Class of 2019

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Frevert, Ute. “Women Worker, Workers’ Wives and Social Democracy in Imperial Germany.” In Bernstein to Brandt: A Short History of German Social Democracy, ed. Roger Fletcher, 34-44. London: Edward Arnold, 1987.

- Fuchs, Rachel and Victoria Thompson. “Feminism and Politics.” In Women in Nineteenth-Century Europe,163-176. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Fuchs, Rachel and Victoria Thompson. “Working for Wages.” In Women in Nineteenth-Century Europe, 61-83. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Sowerwine, Charles. “Socialism, Feminism, and the Socialist Women’s Movement from the French Revolution to World War II.” In Becoming Visible: Women in European History, ed. Renate Bridenthal, Susan M Stuard and Merry E. Wiesner, 357-387. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

- Zetkin, Clara. “Women’s Work and the Organization of the Trade Unions,” Die Gleichheit, 1November 1893, in Lives and Voices: Sources in European Women’s History, ed. Lisa Caprio and Merry E. Wiesner, 371-376. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.