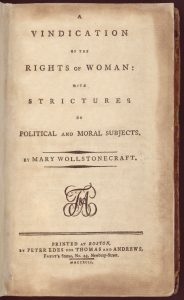

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) by Mary Wollstonecraft

“Let women share the rights, and she will emulate the virtues of man; for she must grow more perfect when emancipated, or justify the authority that chains such a weak being to her duty.” — A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792

The visionary treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published by the English writer Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1897) in 1792. It is one of the first texts by a female author that presented women’s educational as an issue of universal human rights. Wollstonecraft argued that women are entitled to an equal education, one which aligns with their position among society, as mothers, housewives, and laborers. She discusses the idea of “woman’s place” within society and reasoned that, instead of simply being regarded as domesticated housewives living in the shadow of their husbands, women could become “companions” to their male counterparts through the means of equal education prove beneficial for all of society.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was initially published in London during the third year of the French Revolution, which had started in 1789 With all eyes on France, Wollstonecraft wrote her introduction as a response to Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, a French politician, who had drafted The Vindication of the Rights of Men of 1790, a revised version of the French constitution. While Talleyrand agreed that girls should be educated among their male peers, he suggested they be taught only until the age of eight. In her work, Wollstonecraft argued that females should be regarded as full human beings who deserve all the same educational rights as men. Serious social harm and implications, she continued, would result from limiting the capacities of women and their mental and moral abilities.

Wollstonecraft began her work by establishing that she loves man as her “fellow.” However, she is quite clear in that “His scepter, real, or usurped, extends not to me, unless the reason of an individual demands my homage; and even then the submission is to reason, and not to man.” Throughout the text, she continuously restated the idea that man is not necessarily the enemy, yet their actions are what has attributed to these intentional disparities and injustices between men and women. Mentioning the ways in which the writings of specific men throughout history have made women to be “artificial, weak characters… and, consequently, more useless members of society,” Wollstonecraft elaborates on the ways in which men had implicitly assigned women to a place of “weakness” and submissiveness. This, she argued, was a result of educational discrepancy between men and women. She elaborated:

One cause of this barren blooming I attribute to a false system of education, gathered from the books written on this subject by men who, considering females rather as women than human creature, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than affectionate wives and rational mothers; and the understanding of the sex has been so bubbled by this specious homage, that the civilized woman of the present century, with a few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.

In response to the perception of women as submissive and weak, Wollstonecraft argued that this portrayal of women is not attributed to any sort of natural, biological predisposition. Instead, these societal constructions of womanhood occurred through the denial of education imposed on them by men. “Indoctrinated from childhood to believe that beauty is woman’s scepter,” she explained, “spirit takes the form of their bodies, locked in the gilded cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.” Without these indoctrinations of beauty imposed from an early age, women could grow to be much more virtuous, benefiting the good of all. Wollstonecraft stated that women had “always been either a slave or a despot” and either role, “equally retards the progress of reason.”

Wollstonecraft revisits the metaphor of slavery heavily throughout her work, even in regard to women in the middle class. These women, she explained, “May be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent.” She delves into the psychology of women to examine the ways in which one generally accepts the prejudices imposed upon them. She makes the connection between race-based slavery and “gendered bondage,” exposing how these “masters” of women (men) benefit from creating a subhuman female to fulfill their desires. Referring to this form of gendered oppression as modernized slavery, she brings the nebulous “woman question” into the spotlight of civil and human rights and draws awareness to the disparities and injustices which women face.

In many ways, Rights of Woman is interlaced with bourgeois vision of the world and society itself. Wollstonecraft preaches to the values of modesty and labor among the middle class and criticized the “idleness of the aristocracy.” She intentionally and repetitively employs certain keywords as to highlight her concerns of the day, including “tyranny,” “mob,” “despotism,” “liberty,” “natural” “moral,” “virtue,” “vice,” “revolution,” and most importantly “reason.” These quintessential words can be traced back to the Western philosophical movement known as the Enlightenment. The structure of Wollstonecraft’s work was meticulously crafted to appeal to her contemporaries and legitimize her philosophy. Appealing to the literate audience of 18th Britain, which she said suffered from a “fear of innovation,” Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by layering her argument and examples to mimic the layered human experience.

Beyond the general philosophy of the piece itself, Wollstonecraft also develops an article plan for national education reform in opposition to Talleyrand’s plan for France. In Chapter 12, “On Education,” Wollstonecraft proposes that all children should be sent to country day school, receiving education at home “for inspiring a love of home and domestic pleasures.” She argued that men and women should be “educated on the same model.” This shared dynamic of equality between man and woman, husband and wife, is the ways in which society will achieve means of true virtue and morality. She stated:

“So convinced am I of this truth, that I will venture to predict that virtue will never prevail in society till the virtues of both sexes are founded on reason; and, till the affections common to both are allowed to gain their due strength by the discharge of mutual duties.”

Although Wollstonecraft calls for gender equality in some areas, such as in regards to the notion morality, she does not explicitly state that men and women are equal in her works. For her, this equality is really only in the light of God, a conception which is opposed to his comments on the superiority of strength and the submissive female.

Long cited as the fundamental text of Western feminism, the book continues to contribute to modern social thought in many ways. Two hundred years after Wollstonecraft’s death, many issues of which Wollstonecraft raised in her essay continue to evolve. The issues addressed in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman are not all solved. In today’s world, women are still persecuted for pursuing a sufficient education and free sex lives. All in all, there is still a long way to go before women’s rights are truly vindicated.

Rosa Bestmann, Communication Studies, Class of 2018

Sources

Literature and Websites

- Cove, Patricia. “”The Walls of Her Prison”: Madness, Gender, and Discursive Agency in Eliza Fenwick Secrecy and Mary Wollstonecraft’s The Wrongs of Woman.” European Romantic Review 23, no. 6 (2012): 671-687.

- Davis, Walter. “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.” Online Library of Liberty,” at: http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/wollstonecraft-a-vindication-of-the-rights-of-woman (Accessed April 13, 2018).

- Goodman, Dena. “Women and the Enlightenment,” in Becoming Visible: Women in European History, ed. Renate Bridenthal,Susan Mosher Stuard, and Merry E. Wiesner. Third edn., . Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

- Scott, Joan Wallach, “French Feminists and the Rights of ‘Man’: Olympe de Gouges’s Declarations” History Workshop, no. 28 (1989): 1-21.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. London: Penguin Books, 1982.

Images